5.5 DNA match LR

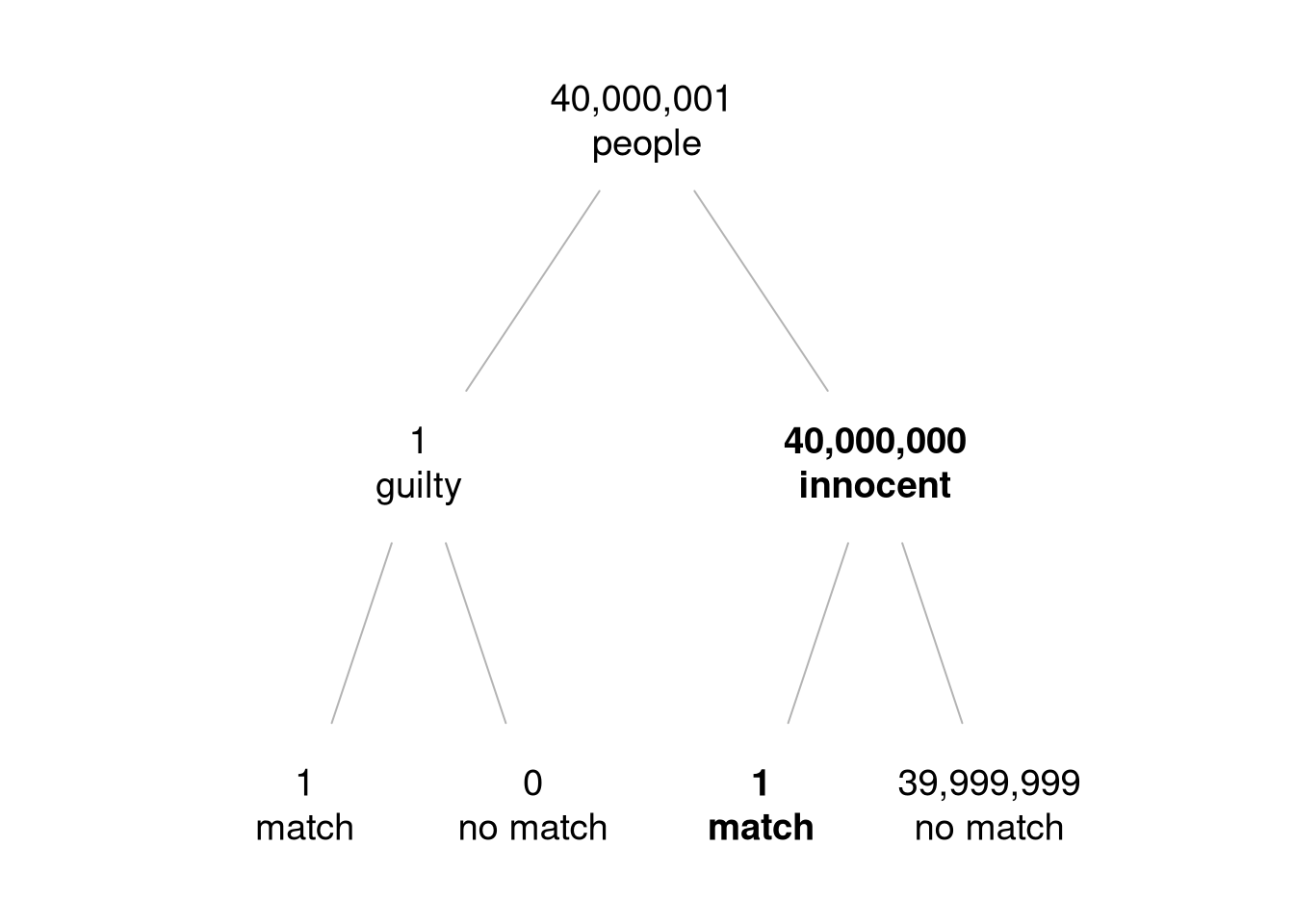

Figure 5.1 displays the expected frequency tree for a RMP of 1 in 40 million in a population of 40 million and 1 people (which includes the guilty individual).

Figure 5.1: An expected frequency tree for the RMP. Out of 40 million innocent people, 1 DNA profile matches. The RMP is 1 in 40 million.

The figure shows that the RMP reflects the belief that out of 40 million innocent individuals from a relevant population, it is expected that 1 will match the questioned profile. In this example, the LR is 40 million. This means that the DNA match is 40 million times more likely if the suspect were the source of the bloodstain compared to if they were not. From the verbal scale in Table 5.3, this LR translates into extremely strong support for \(H_p\) compared to \(H_d\). Note that this LR is for competing source level propositions. If the propositions were moved to the activity level, then the LR could be considerably reduced depending on the case circumstances. It is important to keep in mind the specific competing propositions to which any given LR refers.

\(H_d\) considered anyone other than the suspect. But if there was reason to suspect close relatives of the suspect, such as their siblings or parents, then the RMP as calculated from population frequency databases alone would not reflect the required probability. The genetic similarity between these individuals would mean the probability of a match is higher than the RMP. For this reason, and when there is no reason to suspect close relatives of the suspect, the defence proposition is sometimes constructed as

- \(H_d\): someone unrelated to the suspect is the source (of the questioned profile).

There are other corrective factors that are applied to calculate the conditional probabilities which feed into the LR in the context of DNA evidence, but they are not not mentioned here. To learn more about DNA evidence and resulting LR calculations, please see Nic Daéid et al. (2017) and Puch-Solis et al. (2012).